Zoe Vandersloot doodled squiggly lines with a Sharpie marker on a plain white swim cap. The squiggles, in a rainbow of colors, represented parts of the brain, and Notre Dame junior Karla Casillas, a neuroscience and behavior and sociology major, held up a colorful poster of a brain and described its different areas to Zoe, 7, and her sister Oona, 5.

“Still coloring the frontal lobe?” her dad, David Vandersloot, teased her during the brain health fair at the South Bend YMCA in late March. “You didn’t want to go for the parietal?”

As children and parents approached the table, Casillas beamed and described how much she enjoyed teaching them how the brain works. And at the next table, Kierstin Cousin, also a junior majoring in neuroscience and behavior, noted the same feelings. “As a Notre Dame student, I don’t get to see much of South Bend, so I enjoy participating in community events, especially this one, because it’s so broad and I get to work with many different people.”

Notre Dame’s Neuroscience and Behavior major, developed in 2014, has quickly emerged as the most popular major within the College of Science. For the 2018-2019 academic year, 238 sophomores through seniors have declared it as their major. Because it is also offered to students in the College of Arts and Letters, an additional 94 students in that college are majoring in it. And the work the students do in the community benefits both them and the organizations they serve, inspiring hope and skills in all people to take part in changing communities for the better.

Ruby Hollinger ‘19 (left) and Andrea Alatorre ’19 (right) meet weekly with residents of Hannah’s House in Mishawaka.

Ruby Hollinger ‘19 (left) and Andrea Alatorre ’19 (right) meet weekly with residents of Hannah’s House in Mishawaka.

“Teaching people how to apply information about neuroscience to their own lives makes a difference because it gives us a choice that we didn’t have before,” said Nancy Michael, assistant teaching professor of neuroscience and behavior in the Department of Biological Sciences, and director of undergraduate studies for neuroscience and behavior. “Principles like self-efficacy, perceived self-control, and agency are all well-studied psychological principles that are all centered around personal control.”

Neuroscience and behavior students are applying those principles to brain function and developmental experience with the hypothesis that it will enhance an individual’s sense of control, Michael said. “Once we understand a little more about how our brains actually work, we don’t have to be subject to the world around us… we don’t just have to react, but we can choose how we engage.”

A traditional method of completing research at universities has been to invite people to campus to participate, or to recruit students and staff. But, according to Michael, in certain types of research this has the potential to create a biased sample population because the subjects already have to know the opportunities exist, and have transportation, among other factors. Community-based research bridges a gap because researchers can become imbedded with the stakeholders, truly learning their needs.

“There are many interventions developed in the academy that show a lot of promise in the lab, but when you take them out and put them into the community, they don’t work,” Michael said. “It shouldn’t be hugely surprising, because the population is totally different than the people who came to campus. Our goal is to develop evidence-based interventions on-site that are population-specific, as members of our community working for our community.”

This is why neuroscience students have worked with organizations including Imani Unidad, Center for the Homeless, Hannah’s House, the Robinson Community Learning Center, and the St. Joseph County Juvenile Justice Center (JJC) — and many others — to learn, to teach, and to become partners.

On one afternoon in March, senior neuroscience students Ruby Hollinger and Andrea Alatorre sat in the lower level of Hannah’s House in Mishawaka, about five miles from campus, brainstorming additions to an interactive workbook they’re creating. Hannah’s House is a Catholic agency that offers a continuum of shelter and programming for pregnant and single, sometimes homeless, women. Alatorre and Hollinger have been working with the women at Hannah’s House since the beginning of the fall semester, and knew early on that they wanted to develop a workbook that would help the women reach their goals of independence. Their plan is that the paid staff at the home and future neuroscience and behavior students will be able to implement the project next fall.

“The workbook will have a general overview of mental health, especially depression, anxiety, PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), and will talk about risk factors, prevention, and management of their feelings,” Hollinger described.

Both students, who plan to attend medical school, are learning important research and personal interaction skills. But the women who live at the center are also benefiting, noted Marla Godette, director of programming at Hannah’s House. They trust the students because they have become immersed in the routines there, such as evening dinners, and have developed relationships with them.

“I know the women are impacted because they comment about what they learn,” Godette said, noting that she has has seen how the women absorb the material and use it to improve their lives. “I overheard one of our residents say, ‘Remember last year, what Ruby taught us about the brain and all the stuff that it does?’ That was crazy; I mean, they’re talking about something that happened last year.”

Nancy Michael

Nancy Michael

In addition to completing capstone projects at Hannah’s House, neuroscience students have developed approved research projects at the JJC as well as the South Bend Center for the Homeless. Michael and her students have been collecting data from these projects for two to three years. Results indicate not only significant learning gains of neuroscience and behavior information, but also significant differences in one’s ability to apply these concepts of brain function to their own behavior. Data from the JJC project has been compiled for a journal manuscript that’s currently under review. Michael is also working to compile data from work her students have done at the Center for the Homeless for another journal submission this summer.

Evidence from these pilot programs, along with preliminary evidence generated from the students capstone projects, has motivated the development of sustainable coursework for students, according to Michael. She added, “the real driving factor is the response by the community partners — they see how this information changes the way people think about the choices they get and their options for behaviors moving forward.” Data from pre- and post-assessments in the students’ capstone projects indicates that learning and intention can change behavior after just one “intervention.”

In his 2019 book, “Shortest Way Home,” South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg described his encounter with four Notre Dame neuroscience students in November 2017 when they delivered a presentation about neuroplasticity – the way the brain reorganizes itself throughout a person’s lifetime – to a group of mostly ex-offenders as part of the Peer-to-Peer group program at South Bend’s Imani Unidad.

Buttigieg noticed, just has Godette has with Hannah’s House residents, that it didn’t take the audience long to warm to the material. “The quality of questions they were asking, especially as they applied to trauma and addiction, showed this wasn’t a theoretical discussion to them,” he said during a phone interview. “These were personal questions: How do I give myself more tools to thrive?

“They were really interested, and curious, and searching, and took the students seriously, and you could tell they just lit up when the students engaged with them.”

While engaging with and teaching adults and adolescents about neuroscience has its own nuances, working with younger children is more challenging. Up for the challenge, though, are neuroscience and behavior students Will Smith, a senior, and Will Connolly, a junior, who have been teaching children the basics of brain health at the Robinson Community Learning Center. The center is the off-campus educational facility that’s a partnership between the University and the Northeast Neighborhood in South Bend.

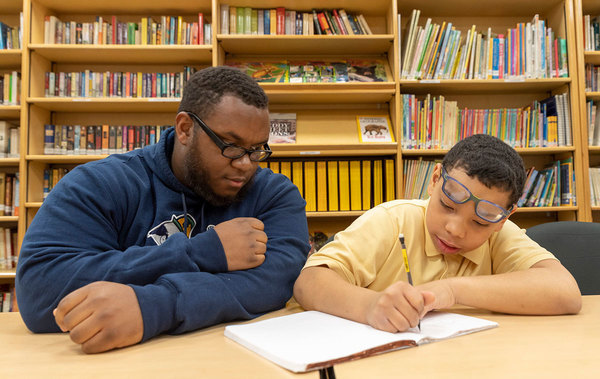

Will Smith ’19 works with third-grade student Alex Batist-Waddell at the Robinson Community Learning Center in South Bend.

Will Smith ’19 works with third-grade student Alex Batist-Waddell at the Robinson Community Learning Center in South Bend.

Every week the duo, known to the children as Mr. Will and Mr. Will, mentor a group of wiggly 8-year-olds in a classroom, talking about the parts of the brain and what each part is responsible for. They then describe the correlation between brain health and behavior. On one afternoon, they played a game with the students, writing their names on a whiteboard and asking how each knew someone else in the class. One by one the students shared their connections, and Connolly and Smith drew lines between each, signifying the pathways in the brain.

“Along with giving them the information about the brain, we teach them about self-care,” said Smith, who plans to become a physician. “Knowing how the brain works will hopefully boost their self-confidence.” Connolly, who also has his sights set on medical school, agreed. “If they are angry but understand the brain, they know to take a step back so they can have a better response,” he noted.

Michael has worked with the University to allow students to repeat their neuroscience research courses multiple times, which not only allows students to more fully complete their research, but also supports her goal of providing continuity to the organizations the students serve. Not only will the organizations see familiar faces over different semesters, but current students can “onboard” their peers for the future.

Asking organizations to allow students to serve and do research with them is, Michael acknowledged, “a big ask.”

“We need to be able to offer sustainable support,” she said. “We are asking them to train new students every semester, so we want to do everything we can to contribute a little more sustainably.”

Overall, the partnerships are examples of how universities and communities can work together, Buttigieg said. As an undergraduate student at Harvard University, he taught a civics class to fifth graders once a week, and said he felt he added value. But he would have relished the opportunity to take the substance of his studies further into the community, as neuroscience students at Notre Dame are doing.

“Frankly I didn’t know very much at all about the community I was living in when I was a student at Harvard,” Buttigieg said. “So I really admire the way the current generation of Notre Dame students – maybe contrary to assumptions, and possibly even contrary to what it might have been like in another era – are really aware of the value of being part of the city in some way.”

He noted that he learned a lot about neuroscience during his brief encounter with students at the Peer-to-Peer meeting, and recognized the relevance that community-based neuroscience education can have in many areas of society. This includes developing well-targeted childhood interventions, supporting people integrating back into civilian life after military deployment, and further understanding substance abuse and addiction.

“After all, government is about serving people, and in many ways, what people ‘are’ is what’s in our brains,” Buttigieg said. “So to the extent that we have a better grasp (of neuroscience), it would probably lead to people making better choices.”

Through the development of the neuroscience and behavior major, Michael is continually evaluating what she can do to contribute making the South Bend area a better, healthier, and more equitable place.

“For me it has become about creating opportunities for my students to really learn that their education has a far greater role than just ‘knowing stuff’ or just ‘being a doctor,’” she said. “Information becomes knowledge only when it’s functional.”

Originally published by at science.nd.edu on May 16, 2019.